Open the small pamphlet flat at the stapled binding, turn the book ninety degrees to read ‘I CAN CALL THIS PROGRESS TO HALT’.

Under a clichéd, definitive ‘Meaning of Everything’ is Ayreen Anastas and Renee Gabri’s hybrid, collaged collaborative text where meanings are contingent on the spatial, temporal, geographic—it depends upon navigation, upon the order in/on/under which our reading occurs. There is no ‘Meaning of Everything’, but a resistance of a totalising order of reading as we move through conversations, citations, questions and maps.

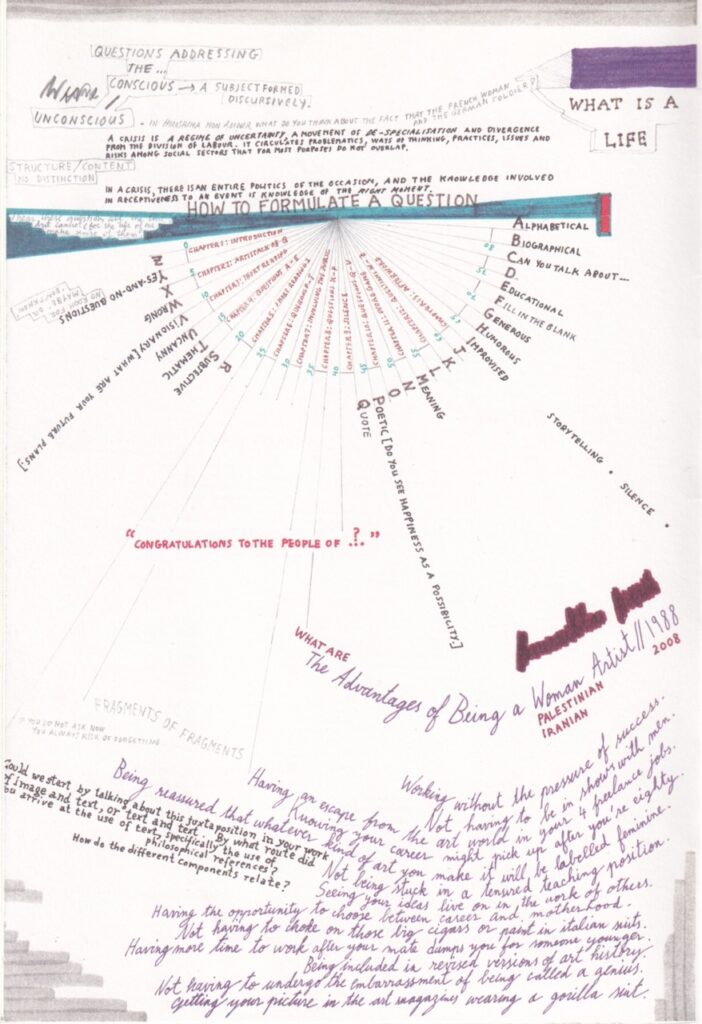

The pamphlet is slight, made up of handwritten texts in different coloured inks, sliced into shapes and patterns. The text begins in the order of prose, one line following the next, then halfway down the page titled ‘Introduction’ we begin to lose the regularity of the line, as the size of the words grow and they begin to overlap and interweave. The text has fractured into collage, questions, diagrams, quotations, maps. Making it from one side to another, that is the centre of The Meaning of Everything.

Written in green—

‘We have changed the names of places and people where necessary to preserve anonymity, but also to render more adequately the fictional features without which documentary, including history and ethnography, could not be.’

Then tucked below—

‘This is a book where artists write about the issues of our times, and talk back to us you, the reader…’

The meaning of the text, The Meaning of Everything, depends upon its order, which in turn depends upon how we read, and where we are—how close, how far. Then on who we are too, whether we see the way over the line from ‘you, the reader’ into ‘us’.

—————

I was surprised to find this pamphlet in The Glasgow School of Art’s Special Collections. I requested The Meaning of Everything, cycled through the rain to The Whisky Bond, just north of the school, visited the collection, read the pamphlet, left. My time with it was short, noticeably so; it was like the pamphlet: slim, flimsy, pale, swallowed into the blank white of the desk.

The day after I opened my bag, where, skulking between my laptop and notebook, I found The Meaning of Everything. I had not planned to take it home, I promise myself, but even so I was glad to be able to hold it again, double check some of my facts, some of the meaning that maybe I’d forgotten. Check that the edges still held up against a background. I carried the text around with me for that week, just small enough to fit in my coat pockets alongside my phone and for it not to be too noticeable, especially if I had my hands in the pockets. I didn’t need anyone to know it was me who had The Meaning of Everything.

—————

Page 1—

‘Finding one’s own voice, this is the central task that faces all of us in our lives.’

We are unsure of the ‘one’ who is speaking. It begins to work as a distinct strategy of the text by displacing a singular ‘I’ in favour of a shared position, and in turn a communally and continually recalibrated ‘meaning of everything’. The textual conversation between handwritings, presumably Gabri’s and Anastas’, gestures towards a real interaction and artistic collaboration; communication and company are embedded in the textual mode of the text, into The Meaning of Everything. Their artistic collaboration began in 1999, ten years before the publication of this text, and they have continued to work together, between forms, art, politics, alert to their relationship as both a critical and creative space.

Perhaps we imagine it as we read, each gap understood as a transformation in the room, air, bodies; the gap is where ‘one’ meets another, to become ‘ours’. The text records a relationship in its handwritten layers, through which a reader will find their way in. We read, in a consistent capital—

‘THIS PERFORMANCE IS ABOUT ADDRESSING A PUBLIC AND INVITING IT TO THINK TOGETHER ABOUT HOW ONE LIVES AND THINKS IN RELATION TO PERSONAL AND SEEMINGLY BEYOND PERSONAL MATTERS.’

But before that, we see above, reading through a neat line—

‘THIS VIDEO IS ABOUT TWO ARTISTS IN THEIR TINY PARIS APARTMENT COOKING THEIR DINNERS WHILE DISCUSSING A WORK THEY THINK OF DOING. THE WORK BEING A FIELD DIARY OF THEIR TRIPS IN LEBANON, PALESTINE AND ARMENIA THE PREVIOUS SUMMER, AND HOW THE ELSEWHERE THERE RELATES TO THE ELSEWHERE HERE.’

The page is in constant reconfiguration. Lines are crossed out in imagined correspondence or dissatisfaction. The aim of the project, its form (‘performance’ or ‘video’), cannot stay still and neither does the text. We as readers are offered a textual history of a project that is unresolved and, in our reading, made ongoing. When a line is crossed out the pen marks a thought, then a changed mind, perhaps a discussion, and a resolution. Gabri and Anastas let the record of their collaboration transform into a performance of it. By letting the reader see through these moments, we enter into the multiple temporalities of the text, and the unsteadiness of its meanings—the fragility of the line itself. It is here, as I read, that the text is made a ‘performance…about addressing a public and inviting it to think together’.

Citing the Guerilla Girls, one handwriting declares: ‘The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist // 1998’, and then another interferes to produce a multiplied and complex question, a question in dialogue with its own state of solidity—

‘[What are] The Advantages of Being a Woman [Palestinian Iranian] Artist // 1998 [2008?]’

The original work by the Guerilla Girls is complicated and resituated for Anastas in 2008. The Guerilla Girls’ humour is made visibly precarious by the texts’ own interruptions, which includes a new date. This was seventeen years ago. What are ‘The Advantages of Being a Woman [Palestinian Iranian] Artist’ now?

The text continues in questions, to sit teasingly on a line of performance, on the rhetorical:

‘How to produce works that address the unconscious?’

‘If I ask you something about colonialism, would that be an impersonal question?’

It is an answer, however, that makes the difference. Here a reader is directly implicated and a ‘reader’ does not exist in a generality, in the ‘impersonal’, so the question is being asked directly to us. This is a knowing technique—

‘The technique of open questioning evoked an equally open answering, like a non confrontational form of common communication giving the option of answering in depth, or indeed with a simple yes or no.’

In this, the text encourages its readers into an ‘open answering’ able to admit as much (or little) depth into the text. However, reading this in 2025, or indeed any time after 1948, it is impossible to leave these questions among the hypothetical.

—————

On the third page of the pamphlet there is a map. It appears disorientated, requiring that you turn the pamphlet ninety degrees anticlockwise in order to read its markings. They are in French. There is also a silhouetted shape of a human head that obscures a third of the map. We are unsure whether the head was cut out of the map or placed on top. Filling in the blank we realise that the shape covers the geographical location of Palestine. A string of text traces the edge of the head as it cuts through the map—

‘CAN ART MAKE MEANINGFUL CONTRIBUTIONS TO A CULTURE OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE? WHAT FORMS WOULD SUCH CONTRIBUTIONS TAKE? (I’M OBVIOUSLY BEING OPTIMISTIC HERE!) CAN THE CONTRIBUTION EXIST ON THE LEVEL OF STRUCTURE AS WELL AS CONTENT?’

It is no mistake that the text snakes the edge of where the head becomes the map, asking where ‘ART’ can become ‘MEANINGFUL’ in ‘POLITICAL RESISTANCE’; it is a question of the text’s own materiality and potential to affect change. The outline of the head, when collaged against the map, becomes a question of borders and statehood. Where occupied Palestine is below, invisible, the reader’s imagination is required to fill it in. By layering this underneath the questions about the meaningful contributions of art to political resistance, Anastas and Gabri orientate their search in/for The Meaning of Everything specifically towards the ongoing occupation and genocide in Palestine. The blank space and the contingent requirement of a reader’s intervention offer a tentative yes towards their questions. It is hopeful, ‘(I’M OBVIOUSLY BEING OPTIMISTIC HERE!)’, but it is also in the hands of the reader.

—————

I make another visit to the collection. In the time between, the occupation and genocide continues. The Glasgow School of Art continues to call it a ‘conflict’ in private and, like many other arts institutions, remains silent. I cross the threshold with the volume tight in my pocket. It no longer makes sense to carry this around with me. It is not making much sense at all. So I decide to return it. I don’t want to keep the text secret. I make my apologies, saying I don’t know how I managed to take it, I didn’t do it on purpose but no one seems to care much. I leave it to dissolve into the shelves again.

The weather is warmer and the sun is trying to shine. My pocket feels empty again. I try to find things to fill the space, find that tissues work, weight wise, with the bonus of practicality. An email goes out two days later. A callout for a lost pamphlet titled The Meaning of Everything. I promise I do not have it this time. No one seems able to locate it anymore.

—————

A reader is essential to the life of a text, to enact the processes of meaning, its knotty diffusion. For The Meaning of Everything a reader is made a constituent part of both ‘meaning’ and ‘everything’. By processes of navigation, readers inform the geography, order and, ultimately, meaning of the text. They write—

‘Read the texts, live with them—perhaps they inspire you to ask the vital questions of our time, too.’

Reading is made a process of living too, or leads towards it. The text is a request for intervention, for a reader with answers. As Anastas and Gabri write, work and live together the text begins a communal invitation. A way to live together that begins in the organisations/reorganisations of text. In an interview with Martha Gosler, Gabri and Anastas describe how ‘we are increasingly being asked to experience our own cities as “tourists”, as consumers, as a kind of “audience” or “spectator” not as a constituent element or public.’[1] Alone in the GSA collection with the text it is cold and the pages are visibly unworn. The Meaning of Everything requires us to become a constituent element of its construction, and also in its ‘meaning’. It is our task, therefore, to decide. On page 6, the definite ‘is’ is crossed out in favour of ‘can be’, so that ‘ART IS RESISTANCE’ becomes ‘ART CAN BE RESISTANCE’. It is our choice as readers whether we step over this line.

[1] ‘Considering the Social, A Conversation on Community’, Martha Gosler with Ayreen Anastas/Rene Gabri in Make Everything New, A Project on Communism, 2006